LOG STRUCTURES IN WESTERN AND CENTRAL PENNSYLVANIA

By Thomas M. Brandon

© 2011

Photographs by T.M. Brandon unless otherwise credited.

INTRODUCTION

In the spring of 1973, I was conducting an exploratory archeological dig of the Moorhead Fort Site, just outside of Indiana, Pennsylvania, on behalf of Indiana University of Pennsylvania. I was a graduate student at the time. One weekend I took my date, Pamela, to the dig site (not exactly an exciting date she admitted years later). While I was explaining some of the findings, Pamela looked up and pointed to an abandoned farm house about 30 yards away from the stone fort building and pointed to the corner of the house where some siding was gone, revealing hewn-logs coming together at the corner to form the walls of the house and asked “what is that house made of – logs?” That began a journey of over 38 years of study to understand not only what that house was and where did it fit in history, but also what the hundreds of other log structures in western and central Pennsylvania meant. This study is a summary of what was found and at my side throughout this journey was Pamela, my wife since our marriage in August 1976.

The western and central region of Pennsylvania experienced a period of robust pioneer development resulting in the settling of vast parts of Pennsylvania’s woodlands. The main surge of the pioneers moved westward out of the Delaware River Valley and southeastern Pennsylvania then south down the great valleys of the Appalachian Mountains beginning around 1725. A main reason the pioneers were able to cut their ties with the Atlantic Ocean coast, boldly move inward and thrive, not just survive, was their ability to quickly build log structures out of the abundance of trees to provide shelter in a harsh and dangerous environment for themselves and their animals. A remarkable number of log structures have survived to help us understand the people of this extraordinary culture.

The region offers a fascinating array of log construction techniques and structures. All but one corner notch associated with the Midland Pioneer Culture is used in the region. The varieties of log structures go from a humble shed not much larger than a dog house to massive bank barns with forebays. The log sizes range from small to massive round white pine found in the northern tier, hewn on all sides or two sides. Structures have space between the logs (chink) with a few having no chink; the chinking used to fill the space is an amazing mix of boards, sticks, stones, mud, straw, and in one building a pair of baby shoes were reportedly found. The academic, historian, or anyone curious about our past will find the log structures in the region a fascinating window into the lives of the people who settled Pennsylvania.

THE STUDY

This study describes the log structures the pioneers built to achieve the settlement of the woodlands of part of the Appalachian Mountains, which includes part of the Ridge-and-Valley section and the Plateau section. Log structures provided newly arriving families with shelter from the weather and wild animals and featured: no need for nails, use of available materials, and built with the basic tools of the pioneer – the axe, adze, and drill. The structures could be built by a single family, clan, or neighbors. The structures required no written plans and could be modified for use by humans, animals, and smaller out-buildings from smoke houses to springhouses and granaries. At the community and business level, the first churches, schools, jails, and mills were made of logs. Log structures helped allow the Midland pioneers to break free from the coast of America and move boldly inland into the Appalachian Mountain woodlands.

The study of folk log construction, also known as horizontal log construction, is exciting because, unlike most artifacts from the pioneer era, log structures have not been moved from where the pioneers used them. The log structure remains intact within the landscape the pioneer who built it intended. Besides the structure itself, which provides valuable information about the specific people who occupied it, the surrounding historic landscape tells it own story of how the family lived, from location of water sources and family dump to the layout of fields, location with other houses in the neighborhood and artifacts found in the ground still in context with their original use. Spend a couple of hours walking around a log farmhouse or barn and the original historic landscape begins to emerge. Old stone walls or split rail fences, roads, wood lines and outbuilding foundations may reveal themselves. Look closely at the surface and you can find pieces of ceramic, glass or metal from the earliest occupation of the land. Coupled with the extensive historical record describing the life of the early pioneers, the story of log structures adds depth and context to our overall understanding of the Midland Pioneer Culture.

THE STUDY AREA SIZE AND TIME OF SETTLEMENT

The study area is comprised of the following Pennsylvania counties: Clinton, Centre, Cameron, Clearfield, Elk, McKean, Warren, Forest, Jefferson, Clarion, Venango, Indiana, Armstrong, Butler, Huntingdon, Blair, and Cambria counties. The study area was settled at different times with the southern counties settled the earliest to the northern counties settled the latest. Southern Blair, Huntingdon and parts of Centre and Clinton Counties were settled by 1780; parts of Clinton, Centre, Blair, Cambria, Clearfield, Indiana, Armstrong, Butler and Venango Counties were settled by 1800. The remainder of the study area counties was settled by 1820 and some sections of Potter and McKean by 1840 (Miller, p. 89, Fig. 7.1). In general, the pioneer population of the southern and central sections of study area counties was higher than the northern counties. The number of log structures still in existence is higher in the southern and central sections of the study area.

The study area is comprised of the following Pennsylvania counties: Clinton, Centre, Cameron, Clearfield, Elk, McKean, Warren, Forest, Jefferson, Clarion, Venango, Indiana, Armstrong, Butler, Huntingdon, Blair, and Cambria counties. The study area was settled at different times with the southern counties settled the earliest to the northern counties settled the latest. Southern Blair, Huntingdon and parts of Centre and Clinton Counties were settled by 1780; parts of Clinton, Centre, Blair, Cambria, Clearfield, Indiana, Armstrong, Butler and Venango Counties were settled by 1800. The remainder of the study area counties was settled by 1820 and some sections of Potter and McKean by 1840 (Miller, p. 89, Fig. 7.1). In general, the pioneer population of the southern and central sections of study area counties was higher than the northern counties. The number of log structures still in existence is higher in the southern and central sections of the study area.

STUDY PURPOSE

The purpose of the study was twofold: to record and preserve basic information on existing structures and pictures of structures in the study area; to analyze the study data using the established principles and findings from the field of cultural geography and folk studies.

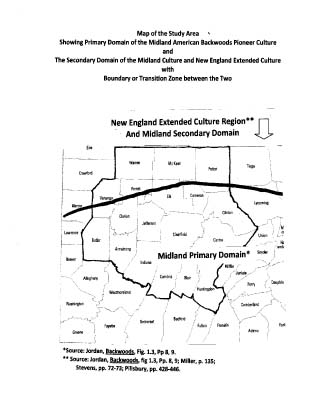

Cultural geographers identified the study area as lying within the Midland Culture primary domain with the northern part of the study area forming a transition border with the Extended New England Culture (Miller, p. 135; Stevens, pp. 72-73; Pillsbury, pp. 428-446). A goal of the study is to determine if log structures and other vernacular structures, both Midland and New England carpentry characteristics, indicate the existence of a boundary zone between the primary and secondary domain of the Midland Culture and the Extended New England Culture.

SPECIFIC CARPENTRY FEATURES OF MIDLAND CULTURE

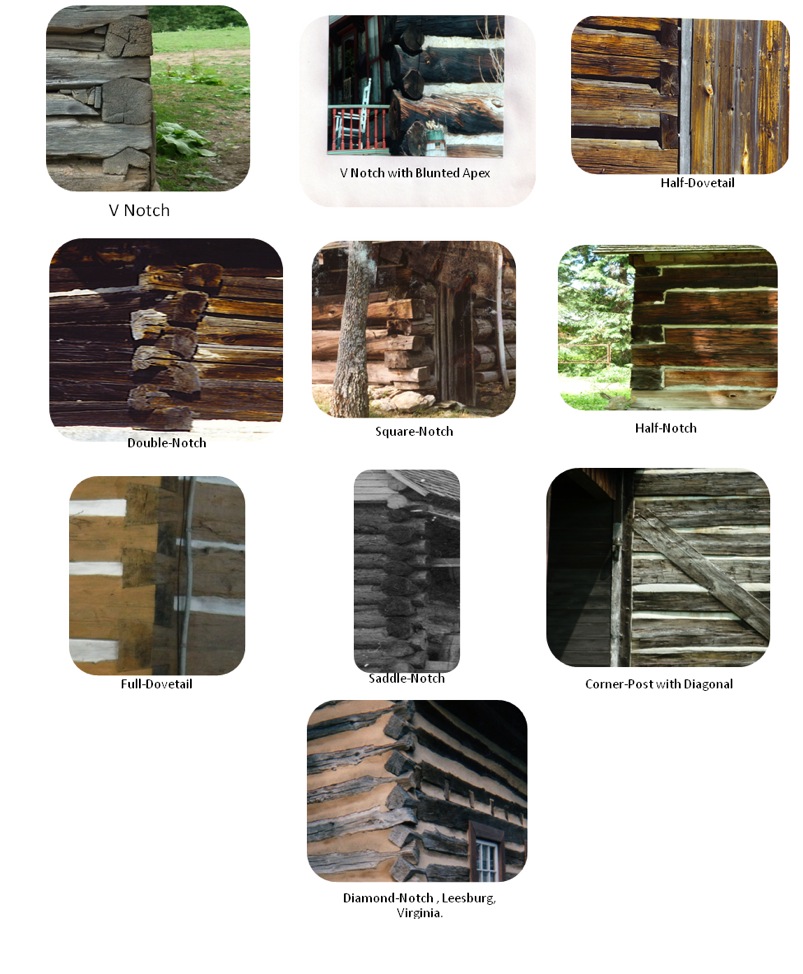

The Midland Culture has specific carpentry features that can be identified through field observations and the analysis of pictures that show detailed construction elements. These construction elements served as the basis for the recording of construction elements in the study. Geographers established a standard taxonomy of terms to describe log construction elements and carpentry features (Kniffen & Glassie, p. 52; Erixon, pp. 13-60); these standard terms are used in this study. Listed below are key carpentry features found in the Midland Culture (Jordan, Log, pp. 178-184).

- Use of round and two-sided hewn logs with top and bottom left round. Hewn logs provide greater interior space than round logs;

- Half-round logs;

- Planking of hewn logs ranging from moderate to thin;

- Space between the logs (chink);

- Chink is filled with a variety of materials (called chinking);

- Notch types (how logs are joined together at the corners) include saddle, V, half-dovetail, full-dovetail, square, half-notch, and diamond. Corner-post, although not a notch, is used in the Midland Culture;

- Board covered gable (no logs in the gable);

- Pennsylvania barn (bank barn);

- Double-crib barn plan, open-passage.

LOG CONSTRUCTION PROVIDED THE PIONEERS WITH ADAPTIVE ADVANTAGES INCLUDING:

- No metal nails needed to secure the logs at the corners;

- The logs provided protection from harsh weather, attack from animals and enemies;

- The logs and chinking provided insulation and fireplaces burning wood provided heat;

- Logs were readily available;

- The weight of the structure was carried by the corners;

- Basic tools carried by all pioneers were used in log construction;

- Amateur carpenters could build log structures;

- Initial structures could be built quickly by a family, clan or neighbors;

- Log construction could be used to meet the pioneer’s needs for all manner of structures.

NOTCH TYPES

The V notch is most common from eastern Pennsylvania westward across the Ohio Valley, including the Shenandoah Valley, and Kentucky.

The V notch is most common from eastern Pennsylvania westward across the Ohio Valley, including the Shenandoah Valley, and Kentucky.

The most complex notches are the dovetail notches. The full-dovetail is not common and found mainly along the eastern seaboard states, particularly Pennsylvania. The half-dovetail is more common and may be the most common notch type. The ‘square’ notch type is a cruder type and occurring mostly along the Gulf Coastal Plain with some examples in the Delaware Valley. The saddle notch is a common notch with the under sided saddle the superior type because water does not collect in the notch. The diamond and half-notch are rare in the Midland Culture. The double-notch type and flared full-dovetail are Alpine-Alemannic type notches but rare or not observed

Logs that do not go beyond the corner of the structure are described as having a “boxed corner” or “box corner” as opposed to logs that project through the corner. Some notch types require that the log project through the corner, like the double-notch. With the cruder structures built with round logs the logs frequently project through the corner; the second phase structures used hewed logs and notch types that allowed for boxed corners (Jordan, Log, pp.18-22).

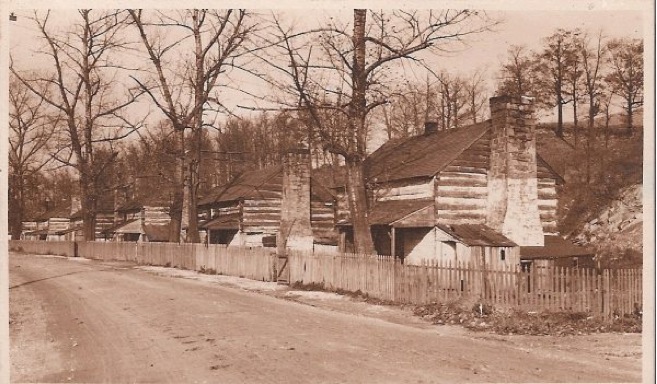

Reproduced by permission of Blair County Historical Society

Worker Housing at Allegheny Furnace, Altoona

Allegheny Furnace was built in 1811 by Robert Allison and Andrew Henderson; it continued in operation until 1836. Reactivated in 1867, it was operated until 1884 by Elias Baker and Roland Henderson. The two-story log houses seen in the picture housed workers and their families. (They no longer exist.)

CONCLUSIONS

- The log structures in the study area confirm that the study area is a part of the primary domain and secondary domain of the Midland Culture.

- The number of log structures found in the northern tier counties was too few to determine if the New England Extended Culture could be identified through vernacular log or non-log structures. At least two log houses and a number of barns and outbuildings did display the non-Midland trait of not having space between the logs (no chink). No chinking is seen in British log buildings like blockhouses and garrison houses. However, just three examples did not establish a widespread pattern. Therefore, the study could not establish existence of the New England Extended Culture through the log structures found. Most of the log structures found in the northern tier counties reflected Midland Culture construction traits.

- The number, variety, and use of log structures reflect a robust pioneer phase in the study area. The variety of notch types in the study is in stark contrast to the, almost, homogenous use of the V notch in Allegheny County and surrounding counties. What is the cultural and historic reason for this? Is cultural diversity seen in other aspects of the pioneers of the study area vs. southeastern Pennsylvania?

- A concentration of log structures built with a half-dovetail notch was found in Clearfield County and surrounding counties; no clear reason for the concentration is known but believed to have a cultural explanation.

- More corner-post structures were found, and continue to be found, in the study area than were predicted by geographers.

- Log structures are being lost at an estimated rate of 1/3 of the total remaining number every 25-30 years. Log structures have the best chance of survival when they have value to the owner –as a house, barn, warehouse or other function or as a family heirloom

- Many aspects of the Midland Culture were practiced by families living in the study area into the 20th

Additional field research is recommended to better understand the log structures in the northern counties of Pennsylvania and southern New York to further explore the influence of the New England Extended Culture on the vernacular structures of the region.